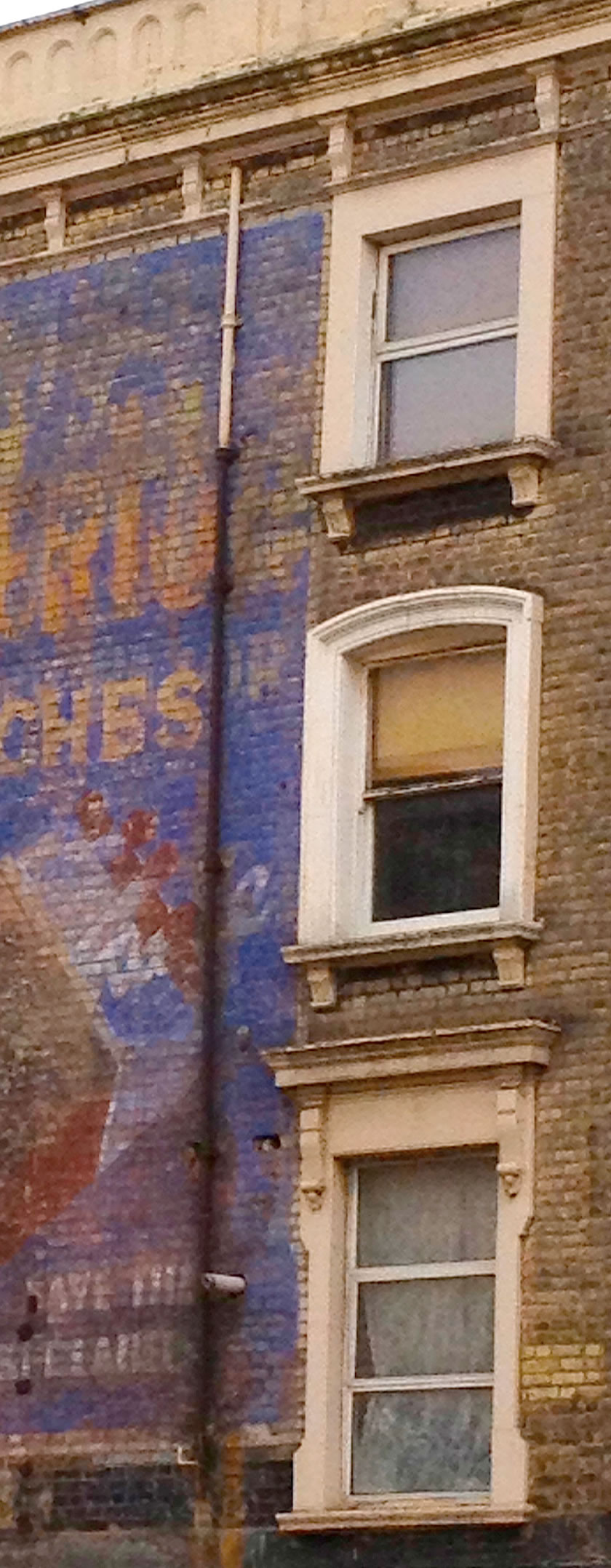

No wonder Martin’s lion looks haunted. London’s full of ghosts – ghostwalks; a city’s worth of cemeteries; ghost- advertising, scabs of paint on brick. The city invoked something, read a grimoire it shouldn’t have. Thatcher’s face recurs at every turn, not in clouds of sulfur but of exhaust, on buses bearing posters advertising Meryl Streep’s celluloid turn as our erstwhile prime minister. Cabinet reports have been released from the aftermath of other riots across the country, 31 years ago. A policy was mooted, they suggest – the point is disputed – of ‘managed decline’ of the troublesome areas. Leaving them to rot.

Does the repressed return, or never go away?

Lionel Morrison considers the past. Few people are so well poised to parse this present, of press scandals, claim and counterclaim of racism and police misbehaviour, deprivation, urban uprising. A South African radical, facing the death penalty in 1956 for his struggles against apartheid – in his house there is a photograph of him with one of his co-defendants, Nelson Mandela – Morrison got out, came to London in 1960. In 1987, he became the first black president of the National Union of Journalists. In 2000 he was honoured by the British Government with what is, bleakly amusingly, still called an OBE, Order of the British Empire.

We sit in his home, between English oil portraits that must be two centuries old, and carvings and sculptures from the country of his birth. Is Morrison hopeful? An optimist?

‘I’ve been thinking about it myself,’ he says gravely, his voice still strongly accented after all these years. ’In a sense, I’m an optimist. But it hits and completely, constantly kicks at this optimism, you understand?’

The ’it’ is everything.

’It’s like a big angry wolf having it over here. And it’s not prepared to move, and sometimes its legs will go, but slow.’ He mimes the animal moving, leaving a little space, a little hole, an exit. ‘And people will say, “Ah, we’ve got it!” And then chop, it goes again.’ His hands come down, the wolf’s grasp closes.

Outside, north London gets on with its dark. There’s an apocalypse more wintery than Martin’s conflagration. At the end of all things, Fenris-wolf will eat the sun. Its expression will be of nothing but greed, and it will look out at nothing.

Lionel Morrison doesn’t sound despairing. But he does sound tired.

’Every time you do something and nothing goes any further, it eats at you,’ he says. ’It starts this bitterness.’ He says the word slowly. ’And I think this is one of the most terrible things that can take place. [...] [M]any become hopeless ... it just breaks them down, and they think, “No, I want nothing more to do with this.” And then you find others who think, “Well, doing this and nothing happens? Well, let us just wait for things to – for chaos, really, to take place.”’

Single page view

Single page view