Find a hole, force your parakeet way in. In the City, moments from Bunhill Fields, the dissenters’ graveyard where Blake and Bunyan lie, near posh ziggurats of the Barbican estate, is Sun Street. There an empty bank, the UBS building, has been taken over by occupier allies of the St Paul’s tent city. They declare it the Bank of Ideas.

‘A Public Repossession’. The doorkeepers, serious young counterculturalists, vigorously enforce a no-alcohol policy. You’re there for a cabaret, slam poetry in what was once an open-plan workspace.

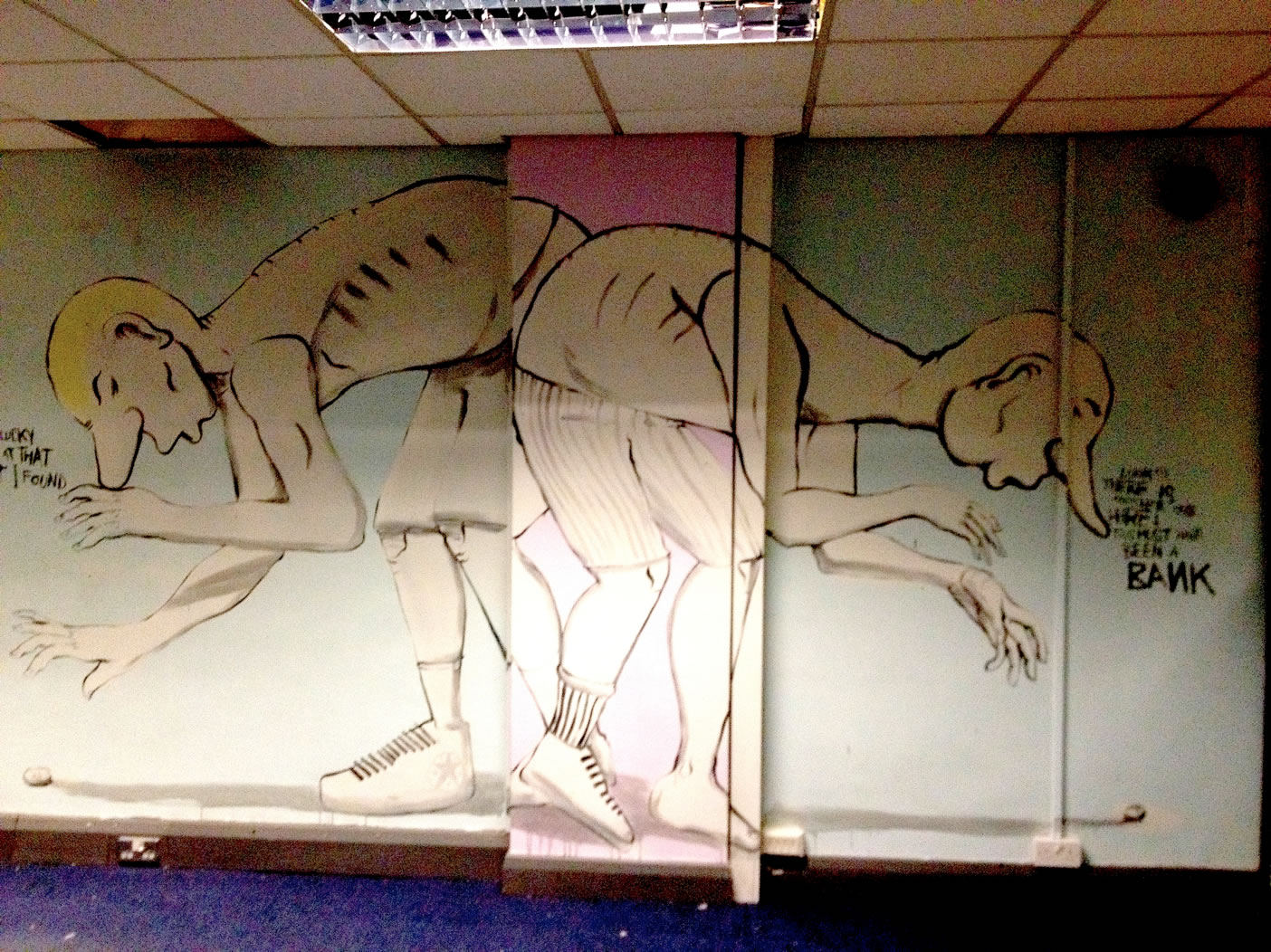

The officeness of the reconfigured rooms is astonishing. Now they contain sleeping bags, placards, chatty gatherings. Sleeping People! a sign warns on one door. A graffitied figure pokes his head through the false ceiling, passes written comment. Downstairs, children play around their parents as the General Assembly discusses the website. Fire fighters politely discuss safety with the new locals.

You ascend an unlit stairwell, very slowly, waiting for the shout, but no one tells you you’re not allowed. It’s startlingly exhilarating. You’re beginning to get it. This is why the psychic economy of squatting, its rejigging of the mind, can end up as important to many squatters as the prosaic financial economy.

Miles south. New Cross. Past a zone of cheap shops and blistered signs, railways and alleyways, a boarded-up backstreet terraced house. You wouldn’t think anyone would answer a knock on this.

But inside, Saul’s house is warm and lit, it’s clean, if a little rough at the edges, there’s food in the fridge, the toilet flushes. It vibes like nothing so much as a student flat. Housemates drift in and out. Ali, a gently-spoken Palestinian refugee, stops for tea and chats about his two years in the notorious Harmandsworth detention centre. What is his status now? ‘I have no status.’

Saul’s hows and whys of squatting. He nods intently and runs through it. He’s done it for years.

Find your place – boards on windows and doors a tell – safely gain entry, sort out wires, do the plumbing, smooth relations with locals and landlords.

Squat well. ‘It’s annoying when people squat badly and it ... creates a bad reputation for everyone.’

The why? Property costs at first, of course, but it goes beyond that now. ’[S]quatting can be seen as just dropping out of mainstream society; avoiding rent, bills, a career, mortgages, responsibility, etc, but it can also be understood in its positive aspect.’ A culture, a collective. ‘As providing or creating space where other types of relationships are possible [...] based on trust, sharing, freedom’.

‘Sometimes’, Saul adds, and he manages to make it seem not forlorn, but good humoured, ‘it even happens.’

Single page view

Single page view